When Texas won the battle of San Jacinto on April 21st 1836, and captured General Santa Anna, the Texas Army wanted to string him up for his atrocities at the Alamo and Goliad. Sam Houston convinced them that General Santa Anna would be more valuable alive. General Santa Anna must have agreed because he signed not one but two treaties. The Treaty of Velasco and a 2nd (secret) Treaty of Velasco. The contents of the secret treaty were mostly revealed, when the first Republic of Texas met and defined the republic's boundary and Texas claim to all the territory east of the Rio Grande from the it's mouth to its source.

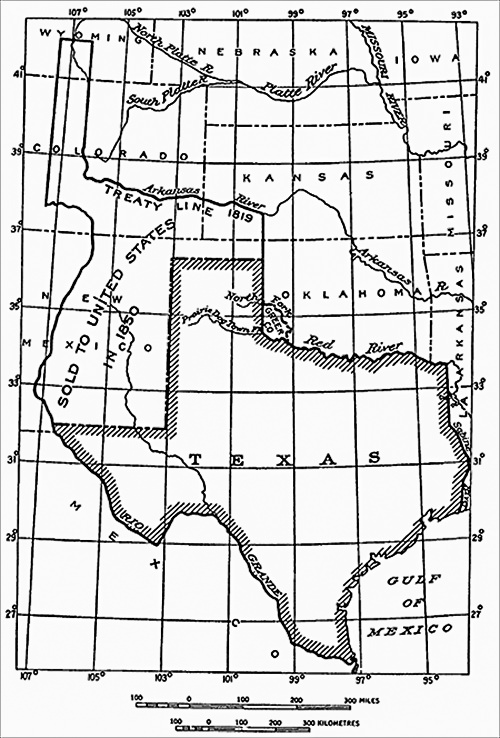

When Texas joined the Union in 1845 it claimed the same boundaries it claimed as the Republic of Texas. At that time, Texas claimed parts of present-day Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, and Oklahoma, as well as the eastern half of New Mexico.

Not six months after Texas became a state, Mexican Troops crossed the Rio Grande in May 1846, as they had several times after Texas won its independence. This time they attacked American troops. U.S. President Polk took offence to this, and declared war on 11 May 1846.

Nicholas Trist was dispatched from Washington to negotiate a treaty of peace. General Winfield Scott halted his army outside Mexico City and offered an armistice to permit Trist to begin his discussions with Mexican ministers. Trist's project of treaty instructed him to secure the Rio Grande as the western boundary of Texas, purchase both Upper and Lower California if he could, but in any event to acquire New Mexico and Upper California. After much negotiation the general content of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was agreed upon, but it took two months to work out the details.

After the Mexican war with the acquisition of New Mexico and California and their slave status of the newly acquired lands unknown, their came demands to reduce the size of Texas. It took congress nine months and a lot of different map configurations to agree on the new boundaries for Texas.

This new boundary, commencing on the 100th meridian in the northeast corner of the Panhandle and running west along the Missouri Compromise line (latitude 36°30') to the 103rd meridian, then south to the 32nd parallel, then west to the Rio Grande, is similar to Texas's boundary with Oklahoma and New Mexico as it exists today.

Texas was compensated for the lost land with ten million dollars in U.S Interest bearing stock. Texas used the money to payoff the existing debt of the Republic of Texas.

If it took nine months to define the boundary lines, and nearly nine years before any attempt was made to run a survey on the ground. It was not until 1858, when Congress authorized the survey and appropriated up to $80,000 to pay for it.

Jacob Thompson, U.S. Secretary of the Interior, appointed John H. Clark to serve as commissioner on the part of the United States, as well as astronomer and surveyor.

Secretary Thompson directed Clark to proceed to San Antonio and on to El Paso with his assistants and instruments "and there prepare to take the field" and conduct the survey "using the most accurate methods known to science in your determinations." Thompson further instructed Clark to transfer his starting point from Frontera, a point near El Paso that had been well established by the United States and Mexican Boundary Commission. H.R. Runnels.

Thompson said, operations commencing at Frontera could be supplied more economically from Fort Davis and Fort Chadbourne while surveying the 32nd parallel, and from Anton Chico on the Pecos or from Fort Union in northern New Mexico while surveying the 103rd meridian.

In September, Texas Governor Runnels appointed William R. Scurry, a lawyer and army officer, to serve as the Texas boundary commissioner. He also appointed Chas. A. Snowden surveyor and John H. Pleasant secretary

Scurry, in the meantime, put together a party of fifteen men, including himself, his surveyor and secretary, six laborers, four teamsters, one ambulance driver, and a herder for the animals, as well as his own outfit and six months' provisions.

Scurry's party and the U.S. commission left San Antonio on November 9, and Scurry planned to leave on the 11th. Clark reported that he and Scurry left San Antonio on the 12th, when Clark's outfit was completed, arriving at the initial point on January 2, 1859. Work commenced the next day.

A base line of 4,750 feet, upon which the whole survey of the 32nd parallel rested, was prepared near the initial point. It took the surveying party ten days to prepare the ground and take repeated measurements. While the surveying party connected the initial point to Frontera by triangulation resting on the base line, Clark fixed the latitude by astronomical observations, which he made himself. Finally, on January 26, 1859, the survey of the 32nd parallel boundary began. By February 14, after the line had been run and marked for twenty-five miles, the party stopped to await the arrival of an escort of two companies of the Seventh Infantry. Chas. A. Snowden, the Texas surveyor, reported that the only difficulty had been a scarcity of water.

Internal conflicts between the Texas commission group and U.S. Commission caused the Texas Commission to withdrawal from the project.

The survey erected a monument on May 22 to mark the intersection of the 32nd parallel with the 103rd meridian. Water had been scarce along the way, frequently having to be hauled by wagon over long distances. The nearest water, after leaving the Pecos, was in the White Sand Hills, a direct-line distance of sixty-five miles.

Following Secretary Thompson's initial instructions, Clark turned north and surveyed the 103rd meridian as far as the 33rd parallel, using only pack mules because the heavy sand precluded the use of wagons.

Clark then went back to the Pecos river and surveyed north in an attempt to mark the 103rd meridian by running offsets. He only made it to the 34th parallel.

At that point, Clark and his party packed up and headed north toward the northwest corner of Texas.

Clark arrived at Rabbit Ear Creek, just outside the northwest corner of Texas, on August 3, 1859, and established an observatory.

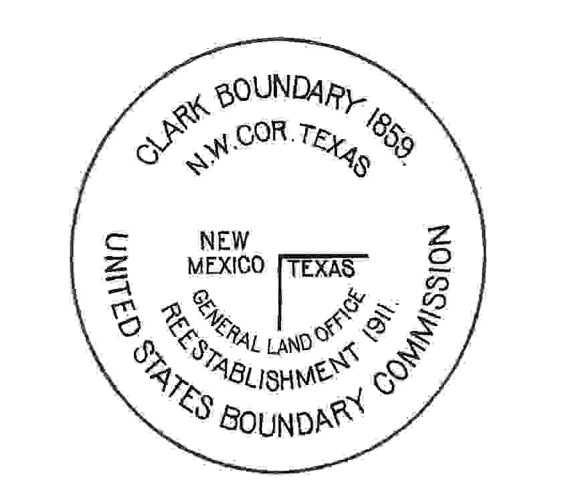

To establish the northwest corner of Texas, Clark first located the south western corner of the Kansas Territory, which then was on the 103rd meridian at the 37th parallel and transferred the point 34.5 miles south to parallel 36°30' for the northwest corner of Texas. Col. Joseph E. Johnston had surveyed the southern boundary of Kansas by chaining in 1857 and erected a monument for the 103rd meridian. Clark had been the chief astronomer on the 1857 survey, had determined that Johnston's monument was 11,582 feet (almost 2.2 miles) too far west. So, Clark then reset the point to 2 miles to the east, unfortunately the actual error was closer to 4 miles too far west. In effect Clark reduced the error in half.

Beginning on August 23, 1859 the party began surveying south, triangulating with reference to prominent landmarks using a large theodolite. It forded the Canadian River and climbed the Llano Estacado near the 35th parallel, finally stopping at the 34th parallel at the end of the season because a belt of sand stood in the way of any further progress.

The Civil War erupted shortly after Clark completed his work on the ground and nothing else was done to survey the 103rd meridian until 1874. In that year John J. Major, a U.S. surveyor, attempted to locate Clark's monument for the northwest corner of the Panhandle. He could not find it.

Major did find Clark's astronomical camp on Rabbit Ear Creek, along with a stone marker, probably intended for the corner monument, that read "103 W.L. [West Longitude] 36°30' L. [Latitude]" The marker had been used as a headstone; on its other side was written "Jane Quin", died 1859.

"Historical Diagram of Texas," Franklin K. Van Zandt, Boundaries of the United States and the Several States, Geological Survey Professional Paper no. 909 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1976)

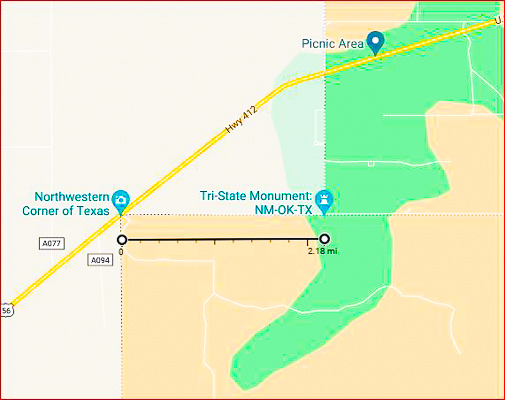

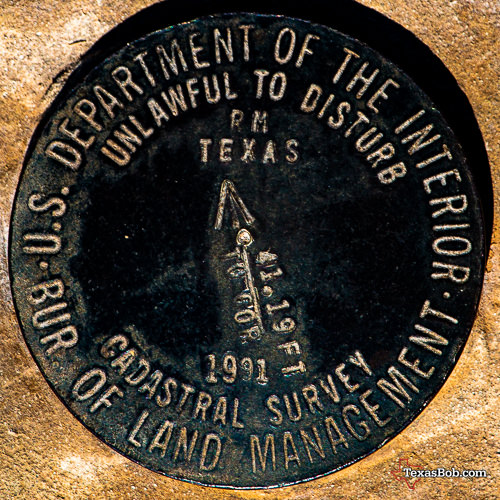

Three State Marker - Texas, New Mexico and Oklahoma

This marker is at the 103 meridian, where the Clark marker was intended to be placed

Frontera - To locate the intersection of the 103rd meridian with the 32nd parallel, Clark was instructed to project the meridian of Frontera, a point established in 1855 by Emory on the Mexican boundary survey near what is today the present intersection of Sunland Park and Doniphan drives and is crossed by the Santa Fe Railroad track and paved roads in El Paso. Thus, the location of the south end of the 103rd meridian became a matter of measuring the computed length of the 32nd parallel.

"Perhaps the Most Incorrect of Any Land Line in the United States": Establishing the Texas-New Mexico Boundary along the 103rd Meridian

Author: Ralph H. Brock - The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Apr., 2006, Vol. 109, No. 4 (Apr., 2006), pp. 431-462

Department of the Interior - BULLETIN of the United States GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 194 - SERIES F. GEOGRAPHY

WASHINGTON - GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1902

The XIT Ranch of Texas And the Early Days of the Llano Estacado - J. Evetts Haley ©1929, 1953, 1967

Handbook of Texas Online - Texas State Historical Association